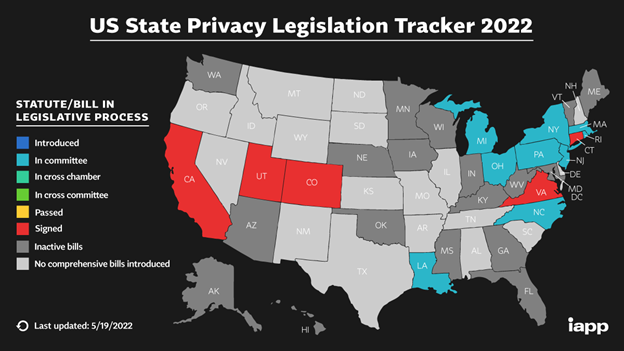

Unlike in the EU, where the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) sets a baseline, the United States does not have a broadly applicable federal law or regulation that governs the collection and use of personal information and data.* Legislative activity in this area is concentrated at the state level, with several states having enacted or now considering privacy laws similar to GDPR:

-

The legislatures of California, Virginia, Colorado, Utah, and Connecticut all have passed state level privacy laws that are effective now or will become effective in 2023. Under implementing regulations, companies operating in these five states must disclose what they are doing with an individual consumer’s data—broadly speaking, it is the consumer’s right to access, delete, or move his/her data.

-

Other state legislatures including those in Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island have proposed privacy laws in committee as of 2022. This means the bill is still in the early stages of the legislative process and the future of the bill is uncertain.

This tracker provides a useful reference.

Not surprisingly, privacy interests in Vehicle Performance Data (VPD) has been a hot topic among consumer protection and other privacy rights groups, as our cars increasingly capture data that can be used to pinpoint a person’s location, movement between locations, and other personal identifying information.

We considered how the five states that have enacted privacy laws have addressed this type of data. The following provides an overview:

California Consumer Privacy Act of 2018 (CCPA), as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act of 2020 (CPRA), effective 2023:

-

If a business collects personal information about a consumer in a vehicle, the business “shall, at or before the point of collection, inform consumers as to the categories of personal information to be collected and the purposes for which the categories of personal information are used, and whether that personal information is sold, in a clear and conspicuous manner at the location.” Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.100(b).

-

Generally, a consumer has a right to opt-out of the sale or sharing of personal information about the consumer, and businesses that sell consumer personal information are required to provide notice and inform consumers of the right to opt out. Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.120. But, an exception to this general rule allows a vehicle dealer and the manufacturer to share vehicle/ownership information for the purpose of repair, provided the dealer and manufacturer warrant no other use. Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.145(g)(1).

-

“Vehicle information” is expressly defined to mean “the vehicle information number, make, model, year, and odometer reading.” Cal. Civ. Code § 1798.145(g)(3).

Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act of 2021, effective 2023

-

The Virginia Act does not specifically define “vehicle information” or include any provisions specific to VPD. “Personal data” is defined to mean any information that is linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable natural person.” It does not include “de-identified data or publicly available information.” Va. Code § 59.1-575. In addition, “sensitive data” is defined to include “precise geolocation data,” and the Act restricts processing of such data without obtaining consumer consent. Va. Code §§ 59.1-575; 59.1-578(A)(5).

-

The Act specifically exempts from its scope “personal data collected, processed, sold, or disclosed in compliance with the federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 (18 U.S.C. § 2721 et seq.).” Va. Code § 59.1-576(C)(11). That Act regulates the sharing of DMV records other than for permitted uses, largely related to law enforcement and safety.

Colorado Privacy Act of 2021, effective 2023

-

The Colorado Act does not specifically define “vehicle information” or include any provisions specific to VPD. “Personal data” is defined as “information that is linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable individual.” It does not include “de-identified data or publicly available information.” Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 6-1-1303(17). “Identified or identifiable individual” is defined as an “individual who can be readily identified” including through reference to “specific geolocation data.” Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 6-1-1303(16).

-

The Act specifically exempts from its scope “personal data . . . collected, processed, sold, or disclosed pursuant to the federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994, 18 U.S.C. § 2721 et seq.” Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 6-1-1304(2)(j).

Utah Consumer Privacy Act of 2022, effective 2023

-

The Utah Act does not specifically define “vehicle information” or include any provisions specific to VPD. “Personal data” is defined as “information that is linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable individual.” It does not include “de-identified data, aggregated data, or publicly available information.” Utah Code Ann. § 13-61-101(24). In addition, “sensitive data” is defined to include “precise geolocation data,” and the Act restricts processing of such data without “clear notice and an opportunity to opt out of the processing.” Utah Code Ann. § 13-61-302(3).

-

The Act specifically exempts from its scope “personal data collected, processed, sold, or disclosed in accordance with the federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 (18 U.S.C. § 2721 et seq.).” Utah Code Ann. § 13-61-102(2)(l).

-

We note in addition that the Utah Motor Vehicle Event Data Recorder Act specifically provides that event data recorded on an event data recorder is private and is the personal information of the motor vehicle’s owner.

Connecticut Act Concerning Personal Data Privacy and Online Monitoring of 2022, aka Connecticut Data Privacy Act, effective 2023

-

The Connecticut Act does not specifically define “vehicle information” or include any provisions specific to VPD. “Personal data” is defined as “information that is linked or reasonably linkable to an identified or identifiable individual.” It does not include “de-identified data or publicly available information.” Conn. Pub. Act No. 22-15 § 1(18). In addition, “sensitive data” is defined to include “precise geolocation data,” which is defined in turn to mean “information derived from technology, including, but not limited to, global positioning system level latitude and longitude coordinates or other mechanisms, that directly identifies the specific location of an individual with precision and accuracy within a radius of one thousand seven hundred fifty feet.” Conn. Pub. Act No. 22-15 § 1(19), (27). “Sensitive data” may not be processed without consumer consent. Conn. Pub. Act No. 22-15 § 6(a)(4).

-

The Act specifically exempts from its scope “personal data collected, processed, sold, or disclosed in compliance with the federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 (18 U.S.C. § 2721 et seq.).” Conn. Pub. Act No. 22-15 § 3(b)(12).

*As explained in this publication, “sector-specific” laws and regulatory power offer some federal protection for minors’ data, credit information, etc.

This post has been updated as of April 21, 2023 and June 6, 2023.

Copyright Nelson Niehaus LLC

The opinions expressed in this blog are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Firm, its clients, or any of its or their respective affiliates. This blog post is for general information purposes and is not intended to be and should not be taken as legal advice.